APPROACHING GOLF STRENGTH & CONDITIONING

Article by Jason Lau

Golf Strength & Conditioning has been a rising topic within the recent years as the introduction of performance based modalities have made an entry within the sport. We have to understand that the modalities previously used (bands, light weight dumbells, balance/stability balls etc) is not enough. While the weight-room is a perfect environment for golf athletes to invest and gain experience towards improving their athleticism, many lack the understanding to moderate their approach in the weight room. If not monitored correctly, the athletes may train in excess, resulting in overtraining, or not enough – resulting in wasted time and lack of stimuli for adaptations. Having the aid of a strength coach helps moderate the amount of work required to drive adaptations while minimizing the drawbacks that come from training. As a coach, our job here is to administer stimuli that are required in the sport without being invasive towards their sport practice.

Throughout recent studies, it has been shown that with purposeful interventions, we can directly influence and achieve higher club head speeds. Golfers such as Bryson Dechambeau and Brooks Koepka are prime examples of how S&C can be beneficial to golfers.

Force Expression in Golf

Swinging the same clubs every day in hopes of increasing club head speed will not provide your body the stimulus it requires to EXPRESS GREATER FORCE. Force expression is defined as a dynamic expression in which we apply force which in turn, causes motion, and Rate of Force Development (RFD) is how fast we can generate said force. By applying the right stimulus in a controlled environment, we can then develop the athletic base that has the potential in which we can generate greater expressions of power. To achieve this, we must apply specific modalities that develops specific muscular qualities. No, we are not attaching a resistance band to a heavier club to practice a swing. The right approach involves identifying the right muscle groups, energy systems, velocities and range of motion seen in sport while pairing the correct exercise variations to satisfy each aforementioned categories. We then must apply the principle of progressive overload towards our training to further push power and strength adaptations. Whether it is adding more weight overtime, general to specific exercises or velocity of the lift all fall under this principle. Progression is key. Exercises such as barbell squats and deadlifts are great options for compound lifts as it allows you to lift the heaviest weight possible contributing to greater maximal strength and force while promoting core stiffness. As for vertical jump exercises, key performance indicators such as box jumps and counter movement jumps can be beneficial for vertical force expression while requiring minimal technical demand.

This brings us to our next point. Gaining mass. Several pro golfers have been seen putting on muscle mass to gain distance in their long game. Gaining mass equates more muscle which in turn, allows us to become stronger and produce more force right? Yes and no. It is not the mass itself that aids in force production but the ability to accelerate said mass that is the main driver towards a faster swing. If strength and swing speed increases as mass is gained, then it is considered a success. However, if mass is gained with no increase in strength and power output, it is then considered counterproductive. There must be a balance to every approach. Too much of a good thing does become a bad thing.

Strength Training in Golf

After discussing the importance of improving force production, lets work backwards and understand how strength plays a part in all this. Strength is the base of which all other qualities such as power are built upon.

As we become stronger, we gain the potential for higher force outputs to further increase our swing speed. If we look at the speed in which golfers swing a club, it is much slower compared to other actions seen in sport. This indicates that golf athletes can attribute more time to grip the floor and generate as much force as possible during the swing. Taking a look at the recorded driving distance in the last 10 years reported by the PGA (see Table 1.1 below) where club head speeds average 93 mph to 110 mph and performed by athletes that have a history of S&C training. Strength can also act as a safety net within injury mitigation. The stronger you become, the greater amount of force your body can tolerate. It is hard to say when an athlete is “strong enough,” this varies from sport to sport and the loads seen within the sport, but a continual strength training should be present within any athlete’s program. This can range from small doses week to week or higher emphasis of dedicated blocks of strength training. Each approach depends on the decision of the coach, competition schedule, athlete’s skill level and what the athlete requires at the time.

Why Not Be Specific From the Start?

Various physical attributes are better developed in a general to specific sequential manner. By sequencing, we can ease the learning curve for the athlete as we begin implementing specific exercises that require technical complexity and base level strength requirements. Furthermore, if we allow no variation - we will risk overtraining, but if we include too much variation, it waters down progress of physical variables and skills. To avoid this, we must apply the principle of general to specific progression towards training and exercise selection.

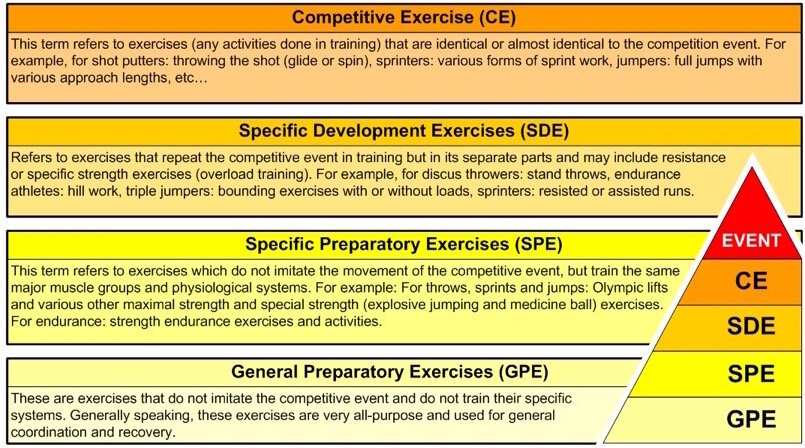

To better classify and label such exercises, I recommend following Dr. Bondarchuk’s, an Olympic coach and competitor, exercise classification below.

As exercise selection becomes more specific, we should begin replicating the movement patterns, muscle groups, loads, direction of force, range of motion, energy systems used and velocities seen in the sport. The goal here is to match the categories listed without falling into the “sport specific” trap and replicating the sporting action completely. A bulk of the work done in the weight-room will be within the GPE and SPE category in Dr. Bondarchuk’s exercise classification. To better clarify this, I have provided exercise examples in the image below (see Image 1.0) with exercises listed from a general (far left) to specific (far right) in relation to the force-velocity curve.

Continual Efforts Are Required

We have often heard the phrase “If you don’t use it, you will lose it.” The same applies towards training and practice. Through Strength & Conditioning interventions, we are able to create adaptations. However, due to residual training effects (popularized by Dr. Vladimir Issurin), describes how long we are able to retain these changes before we lose the qualities gained through our training. In other terms, we must provide a reason for our body to keep these qualities!

With more research and evidence emerging supporting the role S&C plays in the athletic industry, many high level golfers are starting to implement S&C alongside skill sessions to improve their long drive.

As Golf is a performance sport, should we not use performance tools to better the athlete?

I hope this article provided some takeaways towards Strength & Conditioning for Golfers. If you are a golfer looking for sport specific S&C, feel free to contact me through direct message on Instagram or email at Jason@performancepurpose.ca.

For In-Person, Group or Online S&C Coaching Services I provide, CLICK HERE.

Lets start working together to bring your best foot forward this season.

References

Coughlan, D., Taylor, M. J., Wayland, W., Brooks, D., & Jackson, J. (2019, December 15). The Effect of a 12-Week Strength and Conditioning Programme on Youth Golf Performance: Published in International Journal of Golf Science. Retrieved from https://www.golfsciencejournal.org/article/11147-the-effect-of-a-12-week-strength-and-conditioning-programme-on-youth-golf-performance

A;, E. (n.d.). The effects of strength and conditioning interventions on golf performance: A systematic review. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32723013/

J;, H. (n.d.). Competitive elite golf: A review of the relationships between playing results, technique and physique. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19691363/

JC;, A. M. (n.d.). Effects of an 18-week strength training program on low-handicap golfers' performance. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21881530/

Sport, 1. O. (n.d.). Strength and Conditioning Considerations for Golf : Strength & Conditioning Journal. Retrieved from https://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/fulltext/2014/10000/strength_and_conditioning_considerations_for_golf.3.aspx