Agile Periodization: Part 1 - The Concept

Article by Jason Lau

Following a program and having a plan is crucial in any athlete’s development. However, unexpected events can and always be an obstacle in this pursuit. Therefore, we must adapt to these complexities without it impeding on our plans. In Mladen Jovanovic’s “Strength Training Manual - the Agile Periodization Approach,” he describes an agile periodization approach as -

Agile Periodization is a planning framework that relies on decision making in uncertainty, rather than ideology, physiological and biomechanical constructs, and industrial age mechanistical approach to planning (Mladen Jovanovic, 2018).

The purpose of this approach is to find a strategy when dealing with a complex and uncertain domain such as human adaptation and performance. I have found the agile approach to be ideal in real-life situations. Such can be applied throughout various scenarios while accommodating for lack of equipment, fatigue management, athletes missing sessions and so on and so forth. In a world full of complexities and sudden changes such as our present times, we must learn how to “roll with the punches.”

Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approach

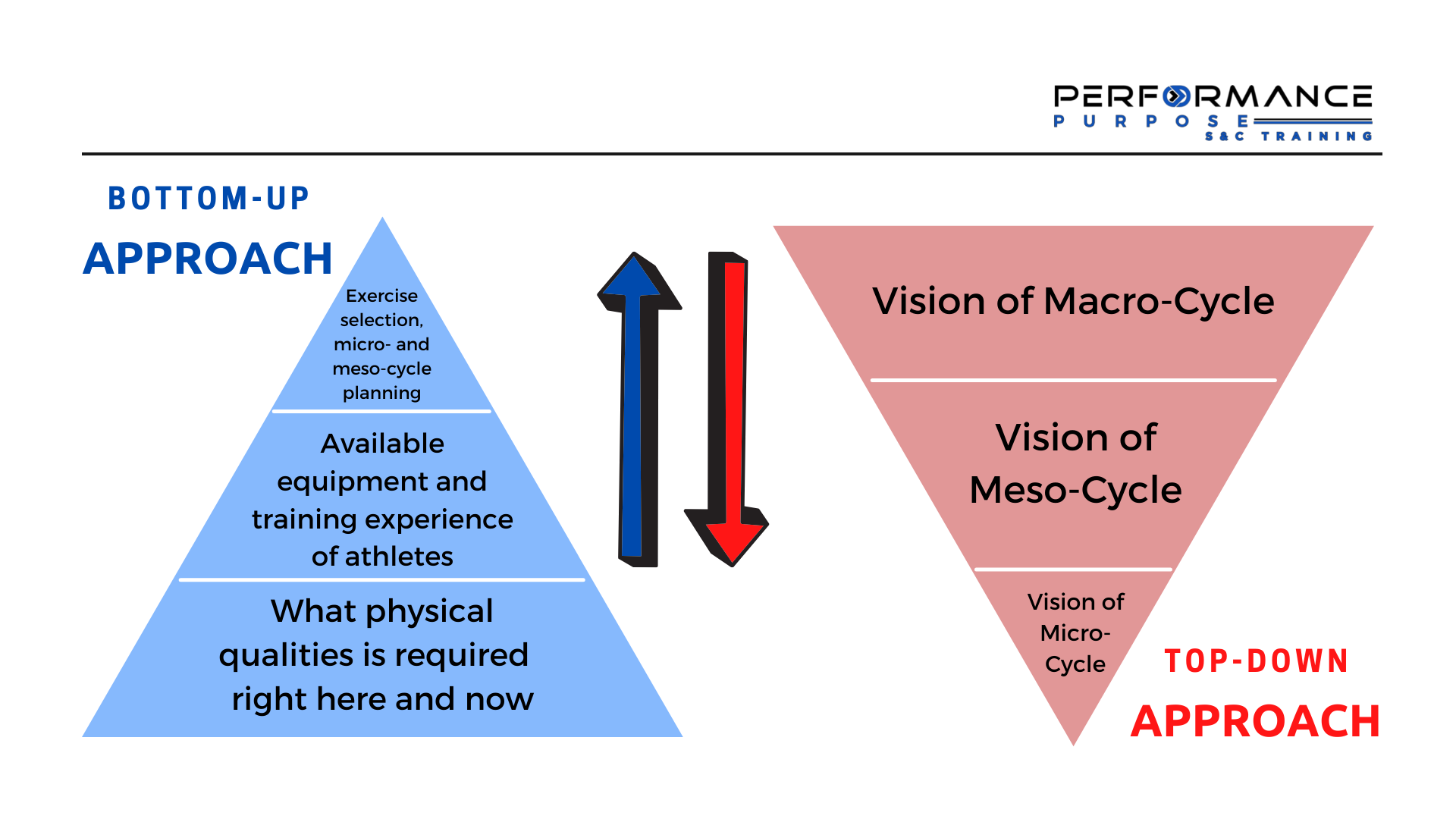

These two approaches complement each other fairly well. From Macro- to Micro-cycle, individual sessions and exercise selection. Each approach is not inherently better than the other, both approaches are meant to be applied synergistically to identify the vision, starting point and the possible routes we can take.

Top-Down

During this approach, we ask the questions such as “What should be done,” “What physical qualities do we need for our sport,” and “Why do we need these qualities.” This requires us to see the bigger picture and will aid us in transitioning from one phase of training to another. This approach also allows us to envision our end goal/outcome and work backwards step-by-step to identify the critical components.

Bottom-Up

This approach asks the questions of “What is available right now?” “What can be done at this moment in time?” and “What does the athlete require right here, right now?” This takes into account of the athlete’s experience level, availability of equipment , the current training/practice schedule and energy availability.

Merging Both Approaches

Now that we have identified our overall plan and what the athlete requires, we can plan the details of the program itself such as the exercises that will give us the adaptations we require. When merging both approaches, we identify the training modalities that can give us the best bang for our buck, end and starting point. The only thing left is to bridge the gap by selecting movements that effectively transition the athlete towards the end goal. This aids to lessen the learning curve and technical demand, helping the transition towards more complex movement patterns. To give you a better idea, I have provided an illustration below shows how both approaches merges at the top and bottom peaks.

The Barbell Strategy

This is an investment concept that suggests that the best way to find balance between reward and risk is to invest your time in two extremes of high-risk and low-risk assets while avoiding middle-of-the-road choices. This middle-of-the-road area, also known as “No man’s land,” is an area where your investments will carry both negative outcomes of both sides of the barbell strategy while gaining little to no positive outcomes. Minimal gain with the chance of higher-than-normal risk is an area where we must avoid.

At the left end of the barbell, we have the conservative approach. This is where we invest 90% of our time in training. Some call this base building, where we build the minimum requirements all athletes must have such as robustness, aerobic capacity, sub-maximal strength base and so on and so forth to protect us from the downsides of training. Such as for any skill development in sport, we must lay a foundation of the fundamentals prior to exposing the athlete to more complex drills/techniques.

At the right end of the barbell is the high-risk high-reward category which takes up about 10% of our training investments. This is the time to experiment with building traits that have a great potential such as speed and power, but carry a higher risk of injury or longer recovery durations. A great example of this are Depth Jumps. Depth Jumps has one of the greatest risk within training through the demands it places on the body but when managed and progressed properly, provides the high stimulus required on developing the Stretch-Shortening Cycle (SSC).

Planning for “Optimality” is Flawed

Plans are nothing; planning is everything. (Dwight Eisenhower, 1890-1969)

Generally speaking, some training programs are done with the goal of getting the athlete from Point A to Point B. This is in no way incorrect, but when planning with the assumption that everything along the way will be stable and predictable is a flaw within itself. Life is unpredictable, injuries are unpredictable, missed sessions or how the athlete performs will ultimately be determined by various aspects outside of practice and weight-room sessions. So how do we plan around these unpredictable events? This is where becoming robust beats optimality each and every time. This is the concept of of robustness implies that we make sure to avoid the downsides (adverse effects) rather than pursuing the upsides of training.

Puzzle vs. Mosaic

Imagine a program where only a different certain physical quality or training effect is prioritized each day. if an athlete misses one training session, they will not be exposed to the missed training effect one to two weeks later and will work against what we know about Residual Training Effects (Issurin V., 2008). Now, if we we plan to micro-dose or train several different physical qualities per session, the athlete will be exposed to the stimulus regardless of missing a session or not. This can be related to The Puzzle Strategy vs. The Mosaic Strategy where if one piece of the puzzle is missing, we must find an exact copy of the piece to fill the gap or else the puzzle is rendered useless. Whereas with a mosaic, can incorporate multiple broken pieces to fill in the gap. From a Strength and Conditioning perspective, the Mosaic Strategy allows us to work around broken pieces (injury, missed sessions, life events) without ruining the whole picture (the vision/outcome goal). This is essential in protecting us from the downsides of such complexities while maintaining physical qualities the athlete will require.

To Summarize

Merging all the forementioned approaches and strategies (top-down, bottom-up approach and Barbell strategy) is only the start of planning the skeletal outlines of a program. To summarize, the utilization of these approaches and strategies help identify:

Identifying the goal/vision and how to achieve it from our current state

Where we should prioritize our time within a session and/or cycle

How to create “robustness” for athletes during unpredictable events

We have all heard someone, whether on social media, your friends, coach or even me, preach the benefits of base building. However, this does not mean we must spend all our time in this particular area or obtain a base prior to investing our time towards other methods of training. Learning to divide our resources in different areas will be another topic I will cover in a later part of this article series.

Make athletes adaptable, not adapted! (Mladen Jovanovic, 2018)