MITIGATING INJURY IN JUMPING SPORTS

Article by Jason Lau

Read part one of my Mitigating Injury Series - “Mitigating Injury in Overhead Sports”

Ankle and Knee Health in Jumping Sports

Injury is unavoidable, it will always be present in recreational and professional sports. An athlete affected by injury may be forced to take weeks or months away from training and their participation within their season may be interrupted. Jumper’s knees and ankle sprains are common injuries seen in jumping and running sports. An athlete affected by these acute and chronic injury will be limited in their ability to run, jump and change direction. I have personally seen the detrimental effects an injury can have on the volleyball and badminton athletes I coach. To remedy this, a well-rounded strength & conditioning program exercising proper load management (of training and practice) and strategic exercise selection that will help achieve injury mitigation alongside athletic performance.

Problematic Areas

The ankle and knee are common problematic areas seen in jumping sports. The high and frequent loads place on the tendons through plyometric and ballistic movements such as repetitive jumps and landings may cause overuse injury if it exceeds the athlete’s load tolerance.

Ankle

Injury:

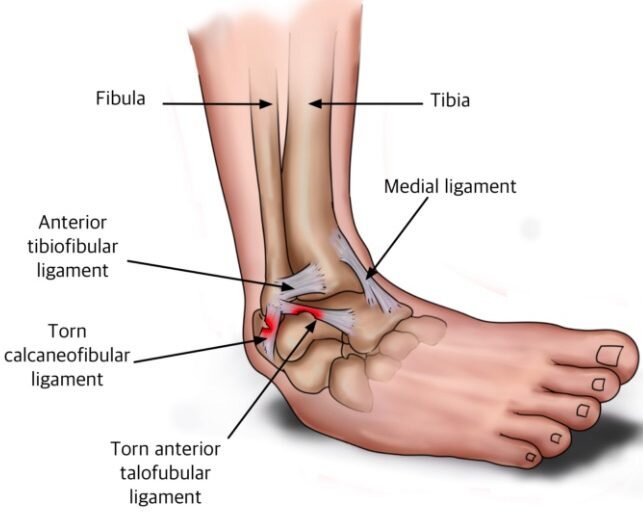

Lateral Ankle Sprain – when the complex of ligaments in the ankle is torn or stressed through a forced plantar-flexion or inversion movement.

Causes:

This injury is caused by a sudden or excessive movement placed on the ankle joint forcing it beyond their normal range of motion. This is commonly seen during jumping and landing movement patterns. This may cause tenderness, swelling, bruising, restricted range of motion and instability to the affected ankle.

How To Prevent Ankle Sprains! Retrieved March 11, 2020,

Knee

Injury:

Patellar Tendinopathy (Jumper’s Knee) – When microtrauma, tears and ruptures occur within the patellar tendon.

Causes:

This injury is caused by cumulative stress from high forces in landing, jumping and insufficient recovery. The forces/stress then exceeds the tendon’s current load capacity resulting in possibly severe stages of degradation over time.

Patellar Tendonitis (Jumper's Knee). (n.d.). Retrieved May 11, 2020

Blazina Jumper’s Knee Scale

The Blazina Jumper’s Knee Scale is used to evaluate the severity of tendinopathy in athletes that have symptoms lasting longer than 6 weeks. Athletes utilizing this scale can give the coach a better understanding of the trauma they may be experiencing and form of actions required to return them back to high performance sports. Athletes may grade their pain on a four stage scale. Stage one refers to pain only after activity, while stage four refers to total tendon disruption. Utilizing the Blazina Jumper’s Knee Scale will help us understand if a reduction of training volume is required, or if we need to seek a specialist for further help.

STAGE 1 - Pain after activity only.

STAGE 2 - Pain/discomfort during and after activity with the subject still able to perform at a satisfactory level (does not interfere with participation).

STAGE 3 - Pain during and after activity with progressively increasing difficulty in performing at a satisfactory level (interferes with competition).

STAGE 4 - Complete tendon disruption.

Review of Mitigation Principles

Taken From part one of my Mitigating Injury Series - “Mitigating Injury in Overhead Sports”

Overuse and overloading are factors that contribute to common injuries in sports. That means strength needs to be addressed so the joints and tendons are strong enough to handle the work capacity it is given.

The key to a successful S&C program is inducing the right amount of training stimulus for adaptions but not too much where it will fatigue the athlete and take away from their sport specific practice. To determine this, a form of athlete readiness monitor or assessment similar to the one shown below (Taken from one of my S&C programs) can be helpful in making these decisions.

Table 1 - Athlete Weekly Assessment

Load Management

Load management is a balance between training, competition/practice and recovery. This needs to be exercised correctly, closely monitored and adjusted on a daily and weekly basis to reduce negative effects of intensive training. If practice has taken a toll on the athlete’s body/joint, then scaling back intensity and/or volume in the weight-room will be necessary. The opposite also holds true. If the athlete is well recovered, increasing load can be prioritized if it does not negatively affect sport specific practice later in the day/week.

Below are several methods that can be used to monitor and aid load management for an athlete.

Daily/Weekly Monitoring and Active Athlete Feedback: Communication is key between a coach and an athlete. Something similar to Table 1 can be used to assess the athlete prior or post training. If the athlete is reports signs of fatigue, then a last minute adjustment in their training is made to accommodate by reducing training load.

Obtaining the athlete’s post-training feedback one or two days later, is just as crucial. This will tell the coach how the athlete responded towards their training and what further adjustments requires to be made.

RPE and sRPE: Rate of perceived exertion or RPE, is a scale used to quantify the amount of effort used during physical activity. Session RPE or sRPE, is a scale for effort used for the session as a whole. For those unfamiliar with the RPE scale, I have provided a table below that will provide further explanation.

Table 2 - RPE Scale

Sets/loads or sessions that rank higher on the RPE scale will require longer recovery periods. Programming activities on the higher end of the scale will need to be exercised strategically. Additionally, if an athlete reports a sudden increase in RPE regarding an exercise targeting the problematic areas, adjustments should be made to lower the risk of injury.

Play Duration and Workload Increase: Sudden increases in practice and workload places athletes at a higher risk of injury. The ability to sustain higher loads has to be achieved gradually. Monitoring both playtime and workload in the weight-room will indicate when and what adjustments can be made to maintain a healthy athlete. If an athlete’s feedback indicates that there was a high focus on intensive jumping or running during a long practice, then workload will need to change to reduce risk of overuse.

Mitigation Movements

Compound exercises should be placed at the beginning of the training session to capitalize on strength adaptions for the specific movement pattern, localized and supporting muscle groups. Performing exercises using all three velocity categories are imperative as each category targets a specific goal.

For the full explanation of the three velocity categories, read part one of my Mitigating Injury Series here – “Mitigating Injury in Overhead Sports”

To be clear (again), this is not for rehabilitation as athletes who are already suffering from injury should have a coach and/or a specialist treat it. If you are looking for any sort of rehabilitation or return-to-play coaching and programming, please click here.

*Please note that the majority of high velocity movements listed can be used for aiding both the ankle and knee joint.*

Ankle

Slow Velocity: Calf Raises (tempo reps).

High Velocity: Lateral Hops, Pogo’s, Calf Drop Raises (see video below), Drop Jumps (see video below).

Isometric/Holds: ISO Calf Raise Holds (various joint angles), Single Leg Balance, any movements utilizing “Floating Heel” (see video below).

Knee

Slow Velocity: Cyclist Squats, Knees-over-toes Split Squats, Lunges, Squats, Romanian Deadlifts, Heel Elevated Split Squats (see video below)

High Velocity: Depth Jumps (various heights), Counter Movement Jumps, Floating Heel Depth Drops (see video below), Kettlebell Catches (see video below).

Isometric/Holds: Heel Elevated Split Squat Holds or any form of single leg, bent knee holds.

Importance of Long Duration Isometrics

Isometric training is an important factor when considering tendon health for the mitigation/management of knee and ankle injuries. Through long duration isometric training (>30 seconds), tendon stiffness and crosslinks changes within the tissue. High velocity training adds crosslinks to increase tendon stiffness for performance, while slower velocity movements or isometrics, break down crosslinks to decrease stiffness, lengthens and promotes collagen to synthesize into the tendon and not scar tissue. This effect, called Creep, promotes direction of tendon tissue alignment, required for positive tendon health. A healthy tendon base is absolutely required to sustain high velocity movements within the athletes’ training and practices.

Movement Progressions and Regressions

For athletes’ currently experiencing tendinopathy, it is crucial to focus on strength work alongside load management. Plyometric, ballistic and strength exercise and volume should be regressed or progressed according the athletes’ current capabilities. Overtime, building plyometric, strength and isometric capacity shall be capitalized to ensure a healthy athletic career. I have included movement progression and regression chart utilizing the mitigation movements I have included previously.

Wrapping it Up

Proper management of workload, exercise selection and athlete monitoring are key variables in an S&C program. By tailoring to each athlete’s strength and weaknesses will ensure the best athletic development for the selected athlete while mitigating non-contact injuries.

To review, here are the principles to follow when mitigating injury:

Closely monitor and adjust training stimulus on daily/weekly basis

Include all three velocities in the S&C program to address all weaknesses

Build capacity of plyometric, strength and isometric workload to sustain healthy development

For Strength & Conditioning Coaching, Personal Training and Powerlifting Coaching, please click here for more information or visit my Coaching Services up top. If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact me via email or Instagram.

References

Chinn, L., & Hertel, J. (2010, January). Rehabilitation of ankle and foot injuries in athletes. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2786815/

Grace, J. (2020, February 1). Case Study: A Systematic Approach to Patellar Tendinopathy Rehabilitation. Retrieved from https://simplifaster.com/articles/patellar-tendinopathy-rehabilitation/

Rutland, M., O'Connell, D., Brismée, J.-M., Sizer, P., Apte, G., & O'Connell, J. (2010, September). Evidence-supported rehabilitation of patellar tendinopathy. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2971642/

Smith, B. J., Smith, J., Bill, Evan, Phil, Phillip, … Mark. (2020, April 18). Deconstructing (and Reconstructing) the Depth Jump for Speed and Power Performance. Retrieved from https://simplifaster.com/articles/deconstructing-reconstructing-depth-jump-speed-power-performance/

Baar, K., University of Michigan, University of Michigan Football, & University of California. (2019, June 27). Dr. Keith Baar on Tendon Health, Rehab and Elastic Power Performance: Just Fly Performance Podcast #156. Retrieved May 09, 2020, from https://www.just-fly-sports.com/podcast-156-keith-baar/

Smith, J., Ryan, & Travis. (2019, July 09). 10 Commandments for Knee Health and Performance (Revised 2019). Retrieved May 09, 2020, from https://www.just-fly-sports.com/10-updated-commandments-for-knee-health-and-performance/

Patellar Tendonitis (Jumper's Knee). (n.d.). Retrieved May 11, 2020, from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/patellar-tendonitis-jumpers-knee

How To Prevent Ankle Sprains! Retrieved March 11, 2020, from https://www.urbanevo.com/training-blog/prevent-ankle-sprains/