Combat Sports: Peaking & Tapering for Fight Camp

Article by Jason Lau

5-8 minute read

Tapering enables fighters to maintain peak physical condition and skills while prioritizing recovery from intense training.

Optimal performance on fight night is paramount in combat sports, where skills and physical preparedness converge for display. Peaking and tapering for a fight necessitate careful management of fatigue, volume, intensity, and recovery to maximize performance. Like fine-tuning an instrument before a concert, a well-planned taper sets the stage for excellence when the bell rings.

Fight camps typically span 5-8 weeks (not including accepting fights on short notice) and involve rigorous skill sessions at high intensity. However, fatigue accumulates during training, especially within a camp. The ultimate goal for fighters on fight night is to showcase their best performance and secure victory, making a proper taper within their strength and conditioning program crucial.

What is a Taper ?

The taper is a short term period where the fighter’s training will be reduced to mitigate fatigue while continuing the maintenance of peak physical characteristics such as conditioning, strength, speed and power. The taper has been defined by Mujika and Padilla as -

“a progressive nonlinear reduction of the training load during a variable period of time, in an attempt to reduce the physiological and psychological stress of daily training and optimize sports performance.”

Variables such as intensity, volume, training frequency or a combination of all three are manipulated to achieve performance increase prior to a competition or season.

Intensity

In the realm of sport science, intensity refers to the load on the bar in relation to the fighter’s estimated one repetition max (E1RM) for the strength lift or Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) of any given exercise or session (sRPE). High-intensity exercises or training sessions taxes the fighter’s nervous system heavily resulting in higher levels of fatigue and longer recovery times.

Volume

Volume refers to the amount of work the fighter has done. Volume for any given exercise can be calculated as the number of sets multiplied by the number of repetitions. Total Volume Load is the total amount of work a fighter has done for a given exercise or the training session as a whole and is calculated by the multiplying the number of sets, reps and weight lifted.

Frequency

Frequency is the number of training sessions the fighter has completed (Skills practice and Strength & Conditioning sessions) throughout the week. It is common for fighters to have two-a-day session, one in the morning and one at night, due to the nature of and skill-acquisition of combat sports.

The Benefits of a Taper

The majority of studies are conducted within Track & Field, Endurance sports, Powerlifting/Olympic Weightlifting, team sports such as Rugby. Although research for tapering in sports is relatively limited and will differ from each sport, we can take successful studies conducted within endurance, strength and power sports to draw parallels and apply it within a fight camp.

Track & Field Athletes

Studies that observe changes to strength and power post-taper in track and field athletes, testing higher- versus lower-intensity tapers both observed increase in both power (Counter-Movement Jump test) and lower strength (mid-thigh pull and 1RM leg press strength test). Both tests indicated improvement to peak force, rate of force development, whole body power and strength performance with tests favoring a high-intensity taper. (1, 2)

Source: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30204523/

Source: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24910954/

Powerlifting Athletes

For literature regarding tapering for powerlifters, shows how a one week taper improved leg extensor peak force increase for experienced lifters (by 8.3%). The same literature states that after a period of OVERREACHING (6 weeks of periodized training) with a one week taper with a reduction in volume (roughly 30-40%) and intensity (roughly 3.5%) did not affect performance. This is perhaps that one week taper is not a long enough taper to properly reduce fatigue, masking athlete performance. (See fitness-fatigue model). (3, 17)

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7552788/

Endurance Athletes

Other literature states that for endurance athletes undergoing the same overreaching phase prior to the taper remained at high intensity with an increase of 20-30% over the average training intensity (at race pace) of normal training was effective in improving performance post taper. (4)

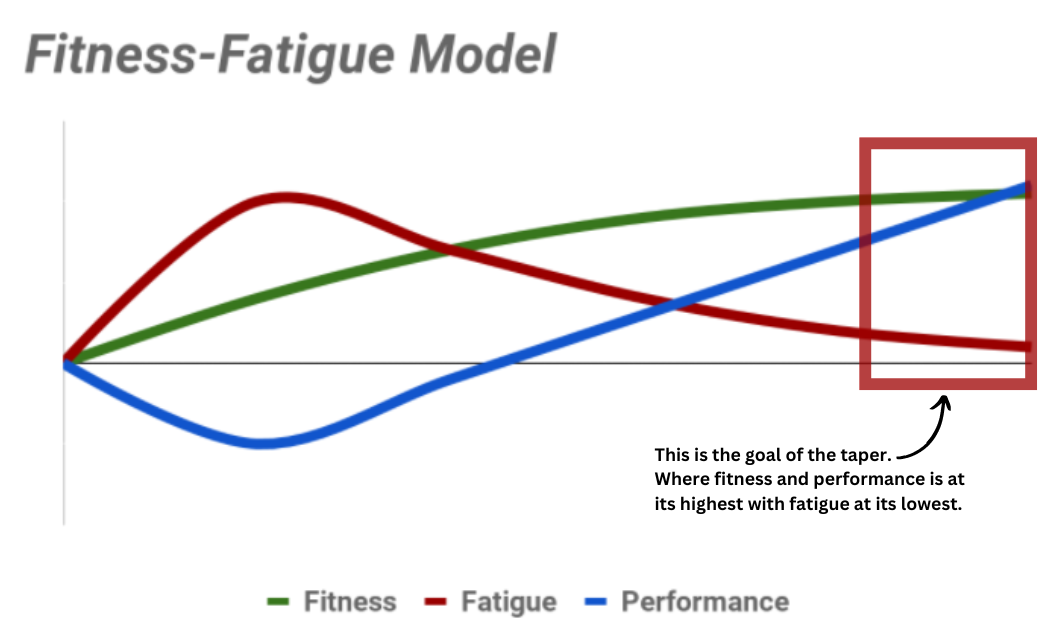

Fitness-Fatigue Model

Before diving into the types of tapers used prior to a fight, one must understand how fatigue masks performance. After training, the fighter will accumulate both positive and negative effects. The positive, meaning fitness, and negative, fatigue and accumulation of metabolic waste products or disruption to hormonal balance. This model shows that the positive effects last longer than the negative when rest and manipulation of training variables are manipulated causing the negative side-effects of training to drop while performance maintains/rises. Too long of a rest and the positive effects will dissipate overtime.(15)

Overtraining & Overreaching

Overtraining

Overtraining is often caused by increase in frequency, volume, intensity of exercise or skills practice without the effect of adaptation and results in long-term performance detriments.

Overreaching

Overreaching is a mild and controlled, short-term period of overtraining where frequency, volume and/or intensity is increased to drive improvement to performance. The athlete can easily recover from this period over a course of a few days of reduced training.

Both overtraining & overreaching are two sides of the same coin. One is a result of poorly planned training paired with inadequate recovery and the other is strategically planned. Literature shows that after an overreaching period (no more than 1-3 weeks), subsequent weeks of improved performance will be achieved. Tests done with weightlifters a week and two weeks after an overreaching period showed not only improvement to performance but tests run on the weightlifters showed lower resting heart rate, blood lactate including positive changes to testosterone/cortisol ratio indicating a positive anabolic state. (5)

Types of Tapers

Tapers is an effective method to enhance athletic performance within the peaking phase through reduction of total training volume (30-70%). This is done through various types of tapers such as Step, Linear and Exponential (Fast & Slow Decay). By understanding the how’s and why’s of each taper, we can then begin to draw similarities and apply it within a fighter’s S&C leading up to fight night.

Step Taper

A non-progressive drop in training load and remains unchanged at the reduced load throughout the training block. This may be a large reduction in training load that spans one-three, maybe four weeks out from a competition. This is most commonly used within sports with prolonged seasons such as rugby. (6, 7)

Linear Taper

A continual reduction of training load for the entire training block in a linear fashion. Examples such as Week 1 - 15% reduction of original training load, Week 2 - 30% reduction of original training load. (6, 7)

Exponential Taper (Fast & Slow Decay)

This is progressive taper that can be categorized as fast or slow decay. This means that for fighters that have minimal time, a drop in training load may happen every several days whereas fighters with longer time frames until fight night can use a drop in training load every week. (6, 7)

All forms of tapers may include low-intensity or small incremental increases in intensity with both showing a reduction in training frequency for enhancement of performance whether in a power, strength or endurance sport spanning from one to no more than four weeks. However, this application is only relevant and effective if the athlete has undergone a period of continual rigorous training previously.

Taper within a Fight Camp

This is a visual example outlining mainly the relationship of total training load and training phases of a fighter leading up to a fight. The precise values of total training load is not accurately represented in this example as training outside of fight camp may be close to, if not, as high as the Overreaching Phase. This will be dependent on the fighter’s training goals outside of fight camp and ability to tolerate and recover form the increased training volume. Prior to entering fight camp, the fighter may have a prescribed deload week hence the drop in total volume load you see.

*For fights accepted upon short notice, a Step Taper may be recommended due to the time constraints placed on the fighter.

After the fighter has completed the overreaching phase of training, the example shows a dip in total volume load leading into a Step Taper prior to fight night.

Again, this is just a visual example of what a fighter’s S&C encompasses leading up to their fight. Specifics and details may vary from each fighter/fight camp.

Conclusion

In conclusion, effective tapering of a fighter’s S&C is essential for optimizing performance in combat sports, aligning training with the demands of fight night.

Although each type of taper can be applied to different sports and athletes depending on their training age, there are several parallels we can draw and apply within a fight camp.

A Taper MUST manipulate the training variables (volume, intensity, frequency)

A taper MUST adhere to the fitness-fatigue model and result in a period of reduced training.

A taper WILL HAVE NO EFFECT if the fighter does not have a previous training block where the fitness is built/being built.

By understanding and applying tapering principles, fighters can ensure they peak at the right time, showcasing their skills and achieving their competitive goals.

If you are a fighter looking to achieve your peak athletic potential, contact me through the link below or DM me on Instagram. Let’s start working together from anywhere in the world.

Reference

Pritchard, H. J., Barnes, M. J., Stewart, R. J., Keogh, J. W., & McGuigan, M. R. (2019). Higher- Versus Lower-Intensity Strength-Training Taper: Effects on Neuromuscular Performance. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 14(4), 458–463. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2018-0489

Zaras, N. D., Stasinaki, A. E., Krase, A. A., Methenitis, S. K., Karampatsos, G. P., Georgiadis, G. V., Spengos, K. M., & Terzis, G. D. (2014). Effects of Tapering With Light vs. Heavy Loads on Track and Field Throwing Performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(12), 3484–3495. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24910954/

Travis, S. K., Mujika, I., Gentles, J. A., Stone, M. H., & Bazyler, C. D. (2020). Tapering and Peaking Maximal Strength for Powerlifting Performance: A Review. Sports, 8(9), 125. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7552788/

Travis, S. K., Mujika, I., Gentles, J. A., Stone, M. H., & Bazyler, C. D. (2020). Tapering and Peaking Maximal Strength for Powerlifting Performance: A Review. Sports, 8(9), 125. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7552788/

Travis, S. K., Mujika, I., Gentles, J. A., Stone, M. H., & Bazyler, C. D. (2020). Tapering and Peaking Maximal Strength for Powerlifting Performance: A Review. Sports, 8(9), 125. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7552788/

Rønnestad, B. R., Hansen, J., Vegge, G., & Mujika, I. (2016). Short-term performance peaking in an elite cross-country mountain biker. Journal of Sports Sciences, 35(14), 1392–1395. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27476525/

Stone MH and Fry AC. Increased training volume in strength/power athletes. In: Overtraining in Sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1998, p. 87-105.

Pistilli, E. E., Kaminsky, D. E., Totten, L. M., & Miller, D. R. (2008). Incorporating One Week of Planned Overreaching into the Training Program of Weightlifters. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 30(6), 39–44. https://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/fulltext/2008/12000/incorporating_one_week_of_planned_overreaching.5.aspx#O5-5-4

MUJIKA, I., & PADILLA, S. (2003). Scientific Bases for Precompetition Tapering Strategies. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 35(7), 1182–1187. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12840640/

Simpson, A., Waldron, M., Cushion, E., & Tallent, J. (2020). Optimised force-velocity training during pre-season enhances physical performance in professional rugby league players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 39(1), 1–10. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02640414.2020.1805850

Munoz, I., Seiler, S., Alcocer, A., Carr, N., & Esteve-Lanao, J. (2015). Specific Intensity for Peaking: Is Race Pace the Best Option? Asian Journal of Sports Medicine, 6(3). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26448854/

Hortobágyi, T., Houmard, J. A., Stevenson, J. R., Fraser, D. D., Johns, R. A., & Israel, R. G. (1993). The effects of detraining on power athletes. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 25(8), 929–935. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8371654/

Bosquet, L., Montpetit, J., Arvisais, D., & Mujika, I. (2007). Effects of Tapering on Performance. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 39(8), 1358–1365. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17762369/

Monitoring Changes in Resistance Training Performance Following Overload and Taper Microcycles - ProQuest. (n.d.). Www.proquest.com. Retrieved April 30, 2024, from https://www.proquest.com/openview/50dd787919cbad3a86999cf984926fe7/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750

Zaras, N. D., Stasinaki, A. E., Krase, A. A., Methenitis, S. K., Karampatsos, G. P., Georgiadis, G. V., Spengos, K. M., & Terzis, G. D. (2014). Effects of Tapering With Light vs. Heavy Loads on Track and Field Throwing Performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(12), 3484–3495. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24910954/

Pritchard, H. J., Barnes, M. J., Stewart, R. J., Keogh, J. W., & McGuigan, M. R. (2019). Higher- Versus Lower-Intensity Strength-Training Taper: Effects on Neuromuscular Performance. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 14(4), 458–463. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30204523/

Chiu, L. Z. F., & Barnes, J. L. (2003). The Fitness-Fatigue Model Revisited: Implications for Planning Short- and Long-Term Training. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 25(6), 42–51. https://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/citation/2003/12000/the_fitness_fatigue_model_revisited__implications.7.aspx